Dedicated to the exploration of madness, mayhem and violence perpetrated by women in film, literature and television.

Monday, February 6, 2017

Deep in the Heart of Dixie

Despite their professed tolerance, their sanctimonious denouncement of any bigotry, there's no group that Let-'em-Eat-Cake Limousine Liberals love to hate quite like white Southerners. They think this country should be run by software entrepreneurs and trust-fund artists without any interference from auto plant workers in Louisville or dock workers in Mobile or mechanics in Savannah. I mean, it's not like they went to the right schools.

The image of a Southerner, one that's reinforced by the Power-Elite beholden media and academia by the kind of people who quote H.L. Mencken and touch themselves, is of some sweaty gun totin' moonshine-swiggin' rebel-flag-wavin' peckerwood named Jimbo, sitting on his morbidly obese behind in a rusty trailer in a crusty "Don't Blame Me, I Voted For Jeff Davis" T-shirt (his "Pull My Finger" shirt got eaten by a possum) watching Jerry Springer re-runs, shooting rats, entering spitting contests and looking for Klan rallies to attend and relatives to date.

And I recently came across this comment from an alleged liberal on Salon.com article:

"My conclusion is that the only way to deal with the 'southern man' is to defeat him, over and over, until he is as marginalized, politically and culturally, as he so deserves to be."

Yikes and gadzooks, this breed of fighting pseudo-liberal has less in common with Thomas Jefferson and more in common with David Duke! Hell, even most of the anti-Southern jokes are just old ethnic jokes with a new accent. There's an irony in there somewhere but I'm not drunk enough to find it.

Maybe it's just easier to target a faceless group of people in another area of the country than to take a long, hard look at the bigotry, ignorance and corruption in your own backyard.

Segregation was de jure in the South, but it was de facto in the North. And while there were riots in Little Rock and Birmingham, the Fighting Pseudo-Liberals conveniently forget the race riots in Philadelphia and New York City in 1964 as well as the violent protests and riots over busing in South Boston that occurred in the 1970s. Birmingham may have had Bull Connor, but Philadelphia had Frank Rizzo. The city MLK cited as being the most segregated wasn't even below the Mason-Dixon line -- it was Chicago.

Maybe it all comes down to the social class. After all, the South is still coping with inherited poverty and all the problems that come with that. When people sneer that they "thankfully live in a more enlightened part of the country" they really mean it's the kind of place where members of the professional class drink frothy lattés in acceptably bohemian coffee houses, crying crocodile tears for the plight of the starving children in Nigeria without worry of having to mix with any of those unpleasant blue collar types because they can't afford the $2,500 a month it takes to rent an apartment in the city limits.

Upon being called "poor white trash," should working class Southerners start telling these jerks to check their class privilege? Upon being jeered at as "rednecks," should we start responding, "Hey, that's pigmentally-challenged regional American to you, sissy britches!"

Then again, I don't know if the descendants of people who followed hellraising John Knox to Ulster and tried to blow off the heads of any government agents who wanted to tax their whiskey really give a damn what the elites think of them.

I don't need no safe space, I'm damn proud to be a redneck. And I'm damn proud that I beat Jimbo in that spitting contest.

And while I'm at it, let's take a romp through the id of the American South with the third movie in my regional horror movie bonanza, shot and produced in Dalton, Georgia and set in Tennessee, FROM A WHISPER TO A SCREAM (1987) also known as THE OFFSPRING directed by JEFF BURR and co-written by him, C. COURTNEY JOYNER, producer DARIN SCOTT and MIKE MALONE.

My love for the Peach State overfloweth. Elitists may sneer at it as a regressive wasteland riddled with poverty, low test scores and peanut stands, but those jerkoids don't like any place that hasn't priced out it's working class. Outside of my native state of Texas, Georgia is that state I've lived in that I love the most. After all, Georgia is the state that gave us FLANNERY O' CONNOR and CARSON MCCULLERS. The Georgians (and Alabamians and Tennesseans, for that matter) I have met and loved share a flair for language and an absurdist sense of humor. Whatever its other faults, Georgia is filled with insane people who want to be your new best friend. And what's better than that?

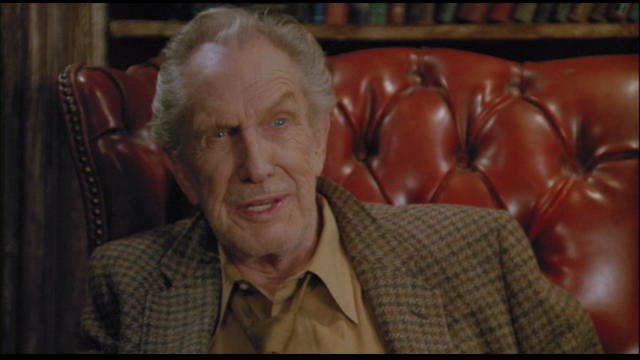

After the execution of notorious serial killer Katherine White (Hammer beauty MARTINE BESWICK), reporter Beth Chandler (my beloved SUSAN TYRRELL) travels to Katherine's hometown of Oldfield, Tennessee to speak with her uncle, Julian, who has the doubly good fortune to be played by the legendary VINCENT PRICE and to be the town librarian. She wants to find out what caused Katherine to embark on a vicious murder spree. He insists that there is no psychological explanation, but something dark and rotten in the heart of Oldfield itself that turns its residents into human monsters. Julian knows where all the bodies are buried -- literally -- and with a deliciously ham-flavored Southern accent, begins to tell Beth about Oldfield's history of violence and depravity. It's like if WILLIAM FAULKNER wrote TALES FROM THE CRYPT.

FROM A WHISPER TO A SCREAM follows the tradition of Southern writers like FAULKNER, FLANNERY O' CONNOR and TENNESEE WILLIAMS. Contrasting Southern gentility with grotesque characters, warped humor and shocking violence, they depicted a South struggling with its identity in the modern age: still haunted from a lost war that wiped out an entire generation of young men, a decaying aristocracy and struggling to come to grips with the decline of an agrarian society being replaced by an industrialized one.

The first story stars dedicated character actor CLU GULAGER as Stanley Burnside, a nebbishy weirdo who develops a crush of Hinckley proportions on the leggy, aloof Grace, his co-worker at the packing plant. Unfortunately, Stanley has few social skills and his overly-enmeshed relationship with his sickly sister, Eileen, has turned him into a bundle of seething resentment. Despite this, Stanley is able to convince Grace to accept a date with him. Unfortunately, he can't reign in the creepiness and spends the evening talking about how their date made his sister jealous, that his mama used to love yams and then makes everything worse by trying to sing a song he wrote about her and forcing her to kiss him while sobbing hysterically. Grace handles this like any wise woman would and attempts to jump out of the car. Unfortunately, determined not to lose the object of his affection, Stanley strangles her to death and dumps her body by the roadside. Though Grace is dead and gone, Stanley's obsession is not, and he breaks into the church where her casket lies...

Yes, my darlings, it all leads to necrophilia, murder and vengeance beyond the grave.

This is one of the stronger segments in the film and probably best remembered because of its sensual fever of perversity as well as a terrific -- and very funny -- performance by CLU GULAGER.

Necrophilia was a favorite trope among Southern Gothic writers. Maybe it's symbolic of the decay and decline of the Old South. Maybe it's due to the tendency of Southerners to romanticize death. Maybe it's a comment on the South's inability to let go of and wallowing in its tragic past.

Maybe those writers just read "Annabel Lee" too many times.

Eileen Burnside, like many Southern Gothic characters, remains insular and focused on the past. She remains in the house away from other people, feigning persistent fevers so that her brother will bathe her in ice water. It doesn't take a PhD in Literature to know what her "fevers" are symbolic of. She obsesses over the memory of their dead father, even suggesting they celebrate his memory at Christmas by getting a Christmas tree draped in black.

Stanley, too, is romantic to the point of obsession. His inability to

In the second story, Jesse Hardwicke (TERRY KISER, the psychiatrist everyone loved to hate in FRIDAY THE 13TH PART VII) is an outlaw on the run (a favorite Southern Gothic character type). Wounded by gunshot, he stumbles into the swamps to be rescued by a mysterious conjureman named Felder Evans. From a revealing scrapbook Felder has conveniently left lying around, Jesse discovers the man is actually over a century old. Ya see, Felder has a potion that grants eternal life. Though he's more than happy to share with his new frenemy, Jesse would rather have all of it for himself.

I've never understood why in movies people are always clamoring for eternal life. Isn't life already long enough?

Underneath the supernatural shenangians there lies a commentary about race and class. The outlaw and the outsider should be allies. In fact, Felder even tells Jesse that he's grateful for his company after being alone for so long. Instead, one tries to use and discard the other for his own gain. Unfortunately for Jesse, karma is a real bitch with rabies.

The third story treks over similar grounds with race, class and witchcraft. Set during the Depression, ingénue Amaryllis falls in love with Steven, the glass-eater in a travelling sideshow. Unfortunately, the owner of the sideshow is a possessive witch (ROSALIND CASH) and the carnies are all outlaws on the run who bargained to become performers in exchange for her protection. It's far from a mutually beneficial arrangement, however, as Steven remarks, "You take more than you give."

Naturally, it does not end well for the star-crossed lovers. It's a pretty grim vision of class mobility: the marginalized are doomed to stay trapped. As Steven tells Amaryllis, "I'm a freak...the carnival is where I belong."

With a backdrop that recalls TOD BROWNING's FREAKS, this segment has the potential to be the most interesting in the anthology but unfortunately it's over as soon as it starts.

The finale takes us back to, of course, the end of the Civil War. A gang of Union soldiers lead by CAMERON (THE TOOLBOX MURDERS) MITCHELL don't want the South's surrender to put an end to their a-rapin' and a-plunderin' so they venture on to Oldfield. They discover, however, that the war has wiped out the entire adult population, leaving the remaining homicidal and disfigured children to run the town. This tale explores similar territory to CHILDREN OF THE CORN as well as one of my favorite movies, THE BEGUILED; it resembles the latter both in its Civil War South setting and in its anti-war sentiment. While it's the powerful that initiate war, it's the defenseless - the children - who pay the price.

When MITCHELL's character protests that the war is over, the leader of the children remarks: "The killing continues...as long as there are big people, there's always a need (for war)."

It's not a surprise that Oldfield's legacy of violence stems from the Civil War. After all, it left deep scars on the American South that are still visible today. When people from other parts of the United States remark (usually condescendingly) about why Southerners can't get over the fact that they lost the war, they forget that the South has still not recovered from repercussions, mainly inherited poverty (which ripples into the educational system, medical care, wages and - well, pretty much everything). Much of the hostility stems from Reconstruction which, instead of being a genuine rebuilding, was a military occupation and austerity program.

There is another point raised in the wraparound segment at the very end of the film. While Julian insists something is rotten in the core of Oldfield itself that turns its residents into human monsters, Beth has another theory: she insists his obsession with Oldfield's depraved history poisoned the mind of his otherwise sensitive niece. Perhaps continuing to wallow in the past is preventing the South from looking for any solutions that would make it a better place to live.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)